Microscopy images and descriptions are courtesy of PhD student Dylan Ziegler.

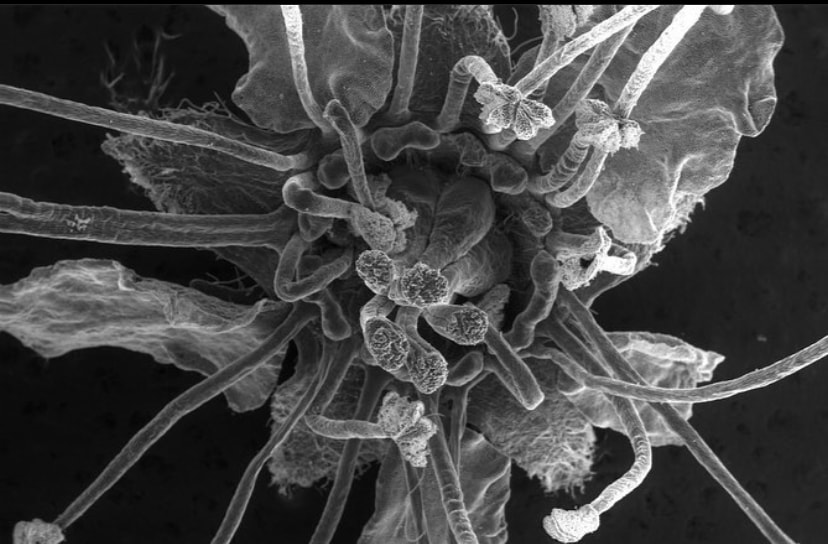

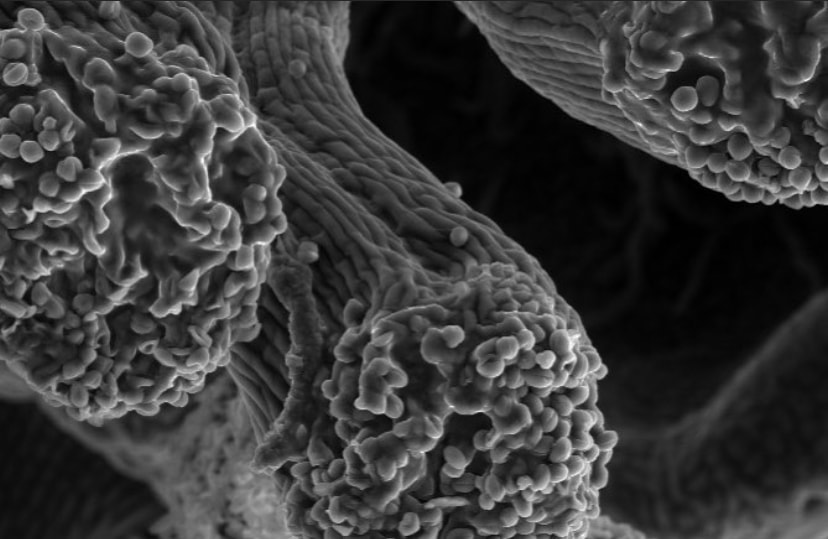

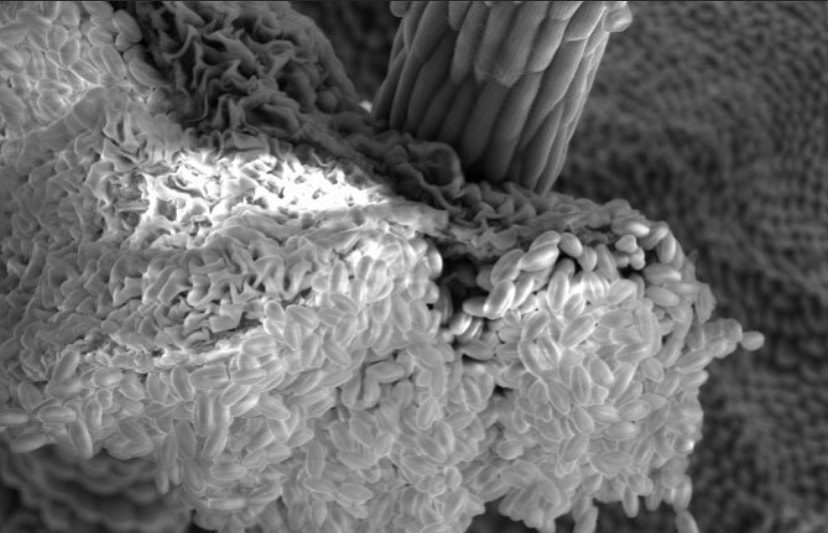

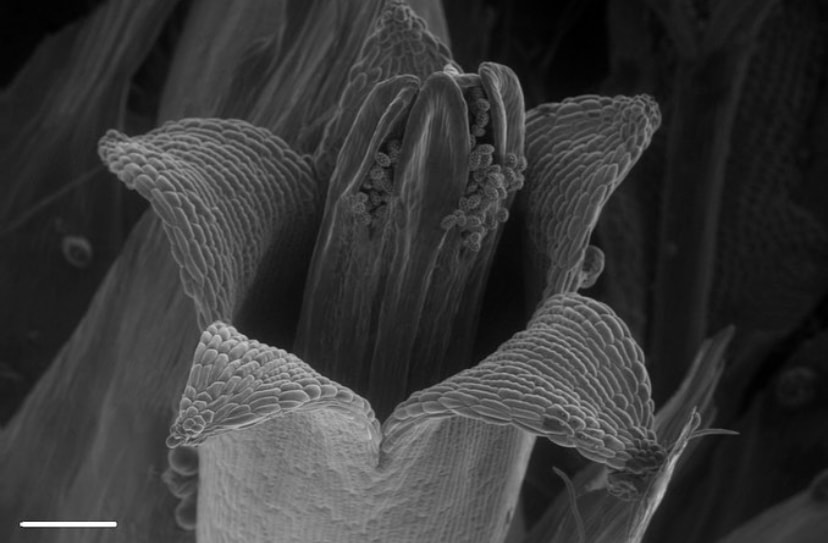

Flowers look a lot different up close! Pictured here is a Spirea flower using scanning electron microscopy. These flowers belong to the Rose family with other plants we rely on, such as apples, cherries, peaches, and plums. This family typically has multiple carpels (female parts) and consequently, many stigmas (second image). The stigma is the receptive surface which pollen grains adhere to. The anther (third image) produces the pollen which will fertilize the eggs within the carpel. Flowers of the rose family typically have so many anthers that they appear hairy!

|

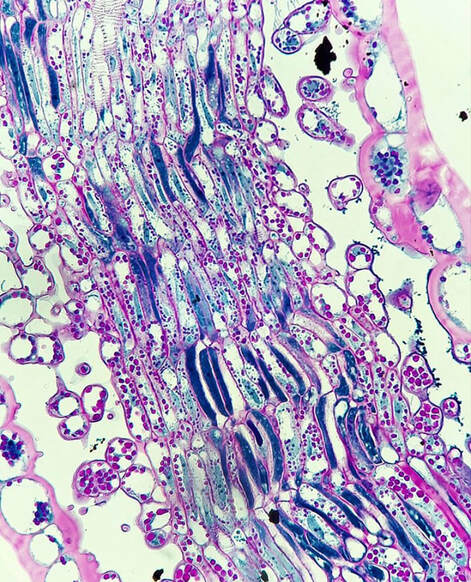

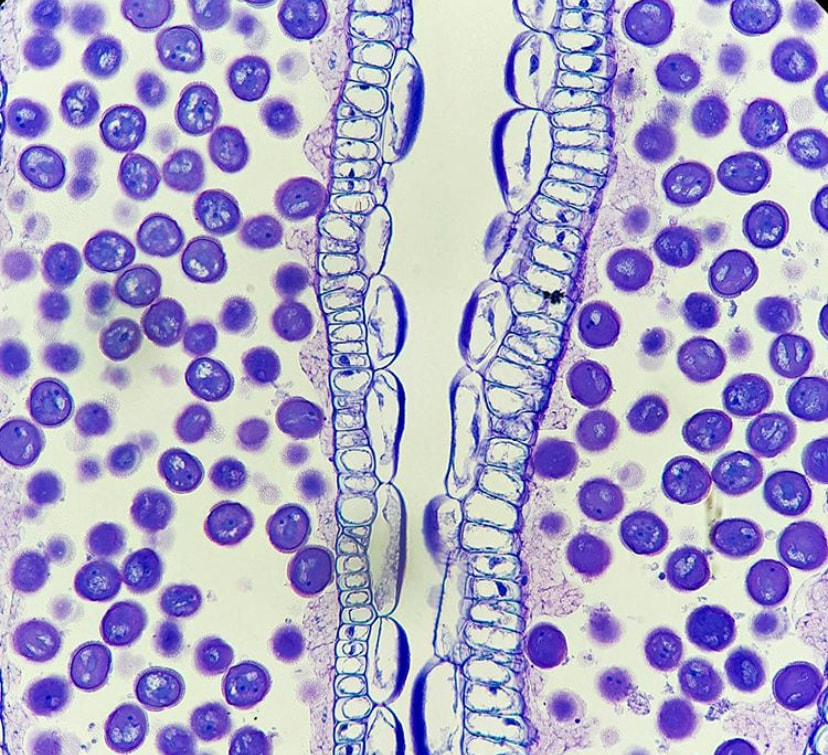

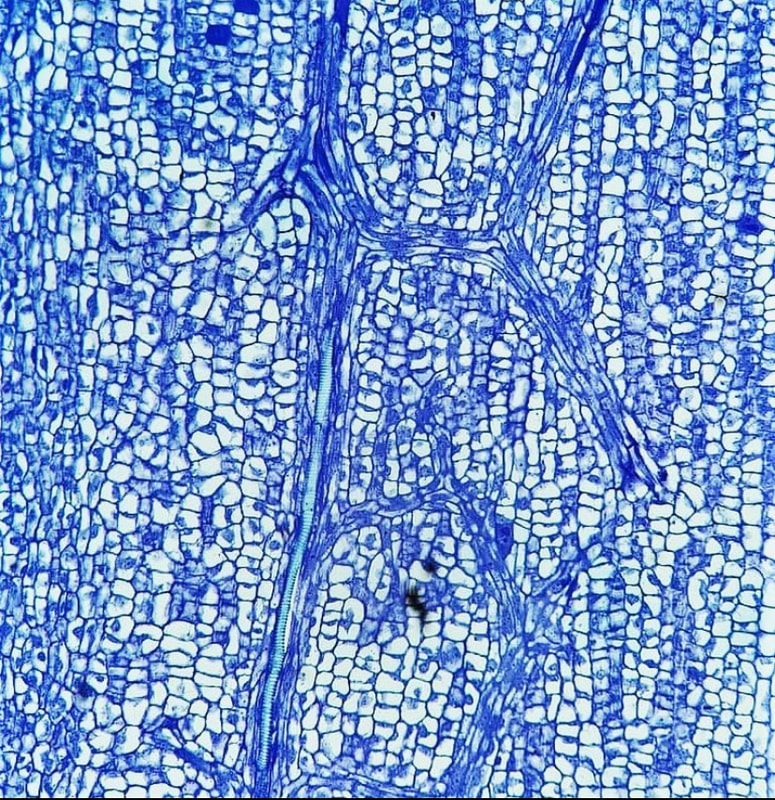

In order for a seed to develop, nutrients and water must be transported from the mother plant into the embryo. Pictured here is the funiculus, a small connection that binds the developing seed to the placenta. The funiculus contains a single vascular trace in most plants and is surrounded by an epidermis. For most seeds, the funiculus senesces late in development and frees the seeds from the placental wall. The funiculus longitudinal section pictured here is of Brassica napus (canola) in early seed development. The central column of elongate cells constitute the vascular trace, with the characteristic rings of the xylem vessels seen at the top of this image!

|

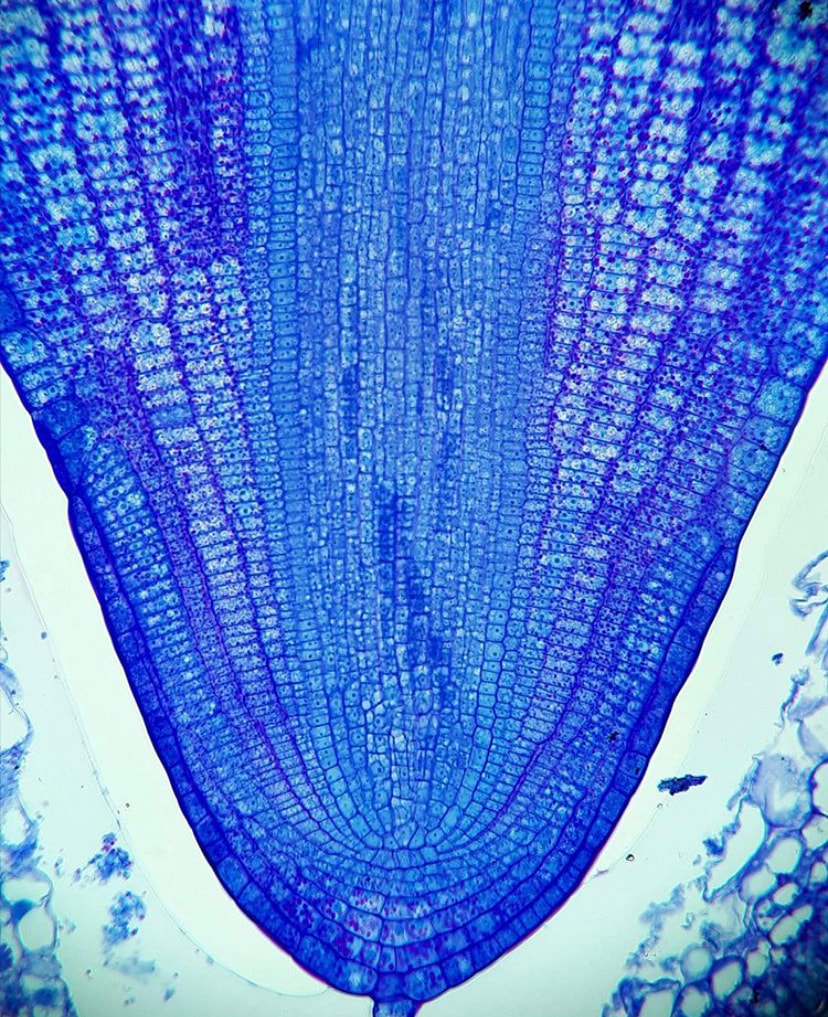

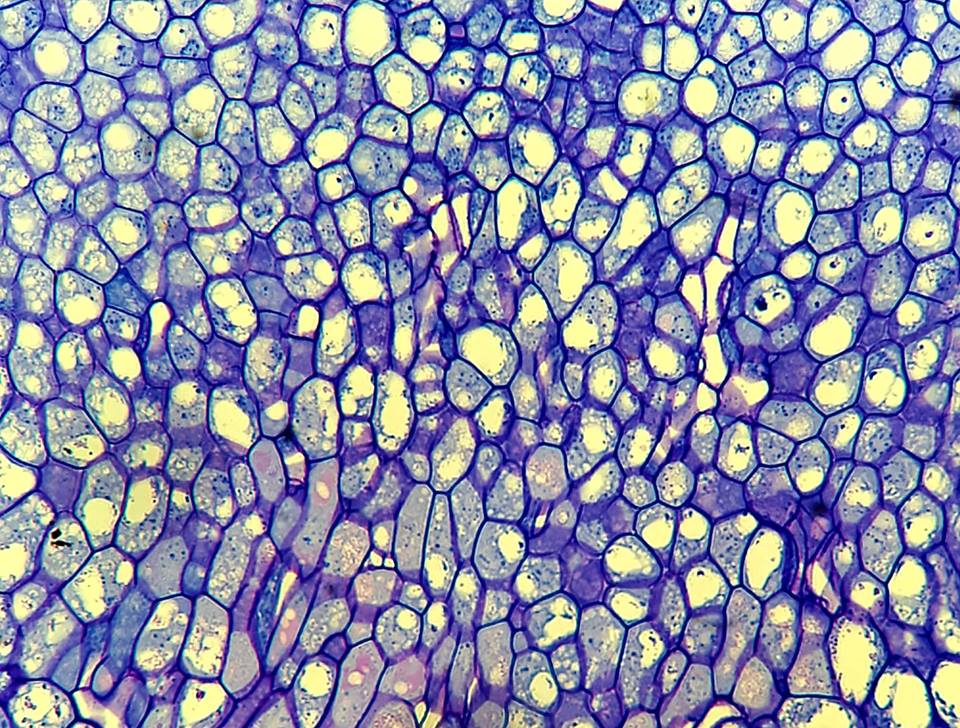

Roots are of course the quintessential anchoring and conducting organ of the plant's body, but how do they look before the seed even germinates? In flowering plants, the root has all its cells fully differentiated once the embryo reaches the heart stage and elongates as the seed matures. It's a complex structure with an apical meristem at the tip and a series of vertically elongated cells that comprise the three progenitor tissues - the ground meristem, the protoderm, and the vascular cambium. The vasculature in the root differentiates early on and fully organizes into the central stele (the central cylinder in this image) early in development. The root imaged here is still contained within the seed and is named the radicle - it has yet to emerge from the seed coat but is fully developed!

|

|

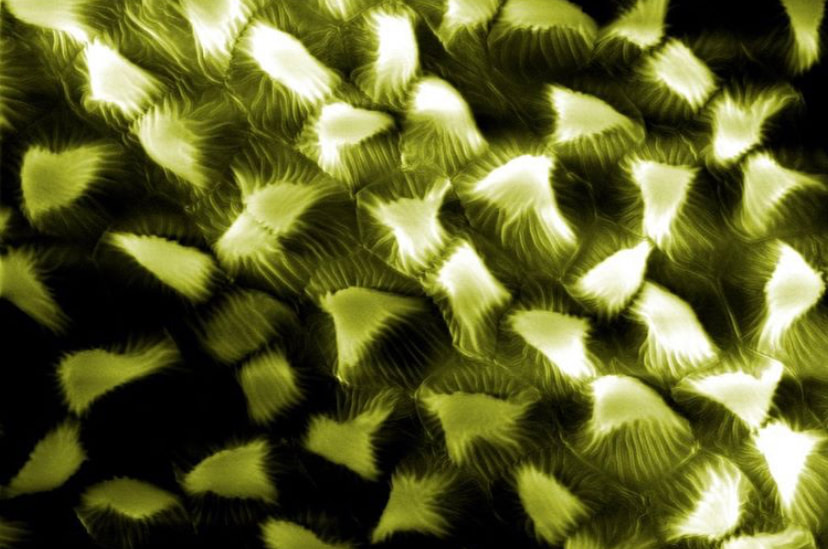

Petals look a lot different close up. Many petals have cellular protrusions which appear as small hill-like cells which are called papillae. Though the function of these cells is not well understood, some evidence exists that these papillae act as tactile feedback for pollinators when they land on the petal's surface. Papillae are only found on the adaxial surface (the "top") of most petals, and are highly discrete in Brassicaceae. Pictured here is the petal surface of Sisymbrium loeselii, a mustard species introduced to most of Canada from Eurasia.

|

Though most of the reproductive biology in the Belmonte lab focuses on seed development, we also look at male development occasionally as well! Pollen is produced within the anthers of seed plants and is dispersed once the anthers crack open. To make pollen, the plant must first develop microspores. Microspores will undergo successive divisions and several differentiation steps to become individual pollen grains. Pictured here are young, developing microspores of canola within the anther sacs - once they are ready to disperse, they dissociate from each other and catch wind or adhere to insects to pollinate other flowers!

|

The above image is Achillea millefolium, or yarrow. Yarrow is a cosmopolitan plant that is a member of the Asteraceae family, the largest flowering plant family in the world! Asters have numerous flowers in one composite head - pictured is a male disc flower. The central column is the anther, which is cracking open (dehiscing) to expose the pollen grains (as seen closer up in the second image).

Wood is one of the primary reasons some plants are able to grow so tall and support themselves – but what about the plants that can’t make wood? Land plants have crafted many solutions to this, but one of the most unique ones exists in Dracaena species (pictured here) and the palms (Elaeis). Dracaena species create a circular band of meristematic cells (similar to human stem cells) that divides to produce larger cells towards the inside of the stem. This process is similar to the development of wood in shrub/tree species, but instead produces independent vascular bundles, rather than the “rings” we use to date trees! Dracaena can expand its stem’s girth and support itself with this method, though it won’t produce any growth rings. These species are common houseplants throughout the world, but are mostly endemic to the tropics.

Pictured here is a longitudinal section of the nectaries of mature Brassica napus (canola) flowers. Nectaries are special structures that protrude from the canola flower, and excrete an aromatic, sugary fluid to attract pollinators. The nectar incentivizes pollinators to visit the flower and consequently spread its pollen. The section pictured is double stained with Toluidine Blue O and Periodic Acid-Schiff, which highlights the abundant carbohydrates in the cells of the nectary!

Canola seeds are contained within a special fruit type of the mustard family: a silique (pictured right). Similar in anatomy to a legume, the silique contains two chambers (what plant scientists call "locules") with seeds attached to a central wall (the placenta) that divides the two chambers. These two chambers are encircled by walls we call the valves. Pictured here is a micrograph of one of the valves, the elongate cells trailing through the wall are the vascular traces, which conduct water and sugars through the plant and provide nutrients for the fruit. The vivid blue, elongate cell is a vessel member with annular rings!

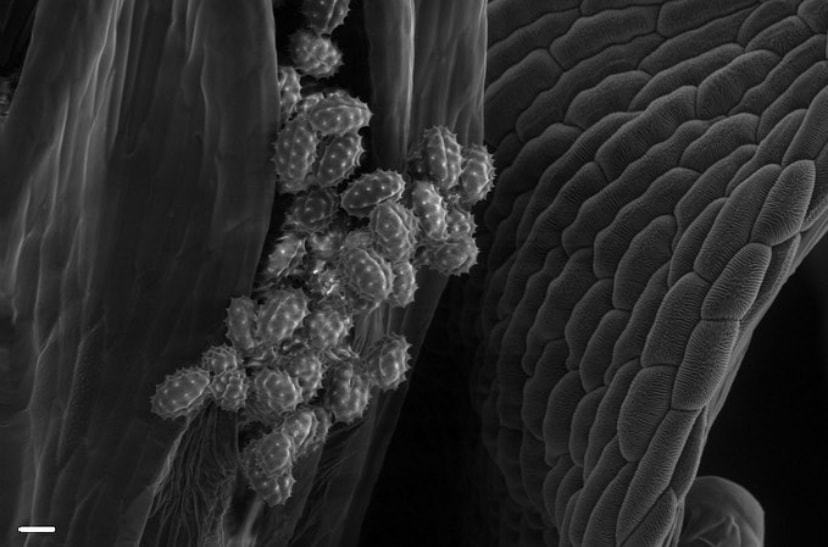

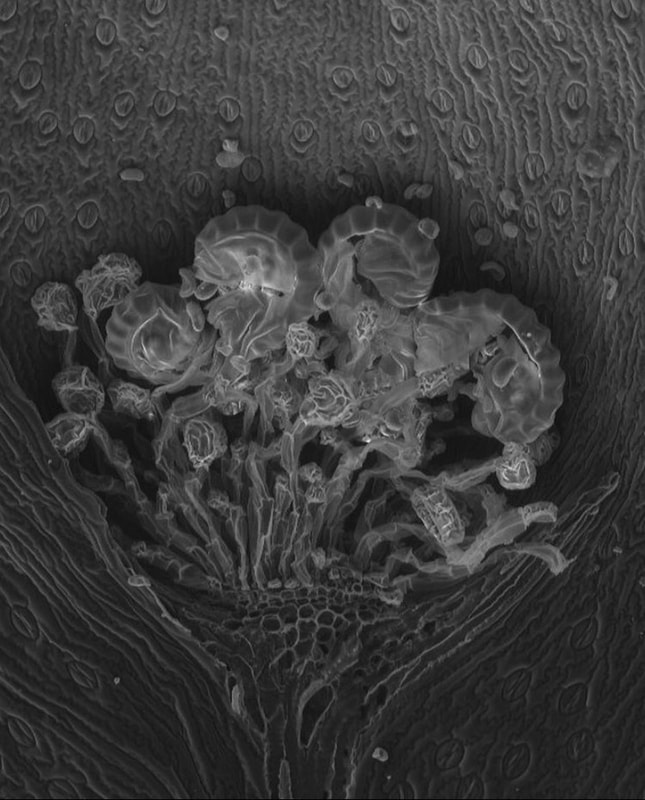

Ferns distribute their progeny using spores, which is a different life stage than the seeds of flowering plants. The spores of ferns are on the underside of their leaves and are wrapped in a capsule called the sporangium. True ferns will actually launch their spores using a catapult mechanism powered by water! Pictured here is a scanning electron microscope image of a sorus (a collection of sporangium) on the underside of a Davallia leaf!

The grass family (Poaceae) is among the most important groups of organisms worldwide. Culturally, grasses are the most important flowering family as they include some of the most economically important crops globally (corn, bread, wheat, rice, etc.). In Manitoba, grasses form the crux of the tall grass prairie ecosystem, and are therefore very important to us regionally as well as internationally. Among the most common grasses are those in the genus Poa, which is imaged here using environmental scanning electron microscopy (ESEM). Grasses have incomplete flowers that are highly modified compared to most flowers we see. Grass flowers lack petals and sepals entirely, and are instead enclosed by modified leaves.

|

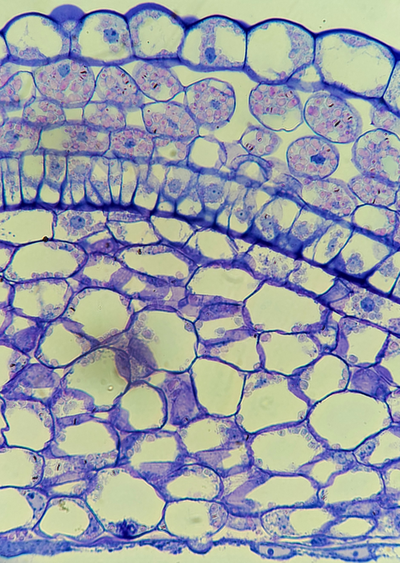

One of the primary focuses of the Belmonte lab is studying the canola seed. Like many flowering plants, the canola embryo is encircled by two integuments which form the seed coat. Pictured here is a maturing seed coat stained with Toluidine Blue and the Periodic Acid-Schiff reagent. The cell layer on the lower surface is the inner seed coat, and is separated from the outer seed coat by a distinct row of columnar cells called the palisade layer. The outer seed coat contains abundant starch granules (pink dots). The seed coat is one of the most important innovations in land plants - it waterproofs the seed and protects the embryo from harsh environmental changes!

|

Seed plants account for greater than 90% of all and plant diversity in the world and are on of the greatest evolutionary milestones in the world - paving the way for tremendous species diversity in land plants. In this image, an early developing seed is stained with Toluidine Blue and Periodic Acid Schiff's reagent to highlight cellular components. The circular structure is the embryo, which is embedded in the seed coat via the suspensor (the stalk subtending the embryo). The two integument layers protect the developing seed, and will inevitably fuse together to create the impermeable seed coat.

|

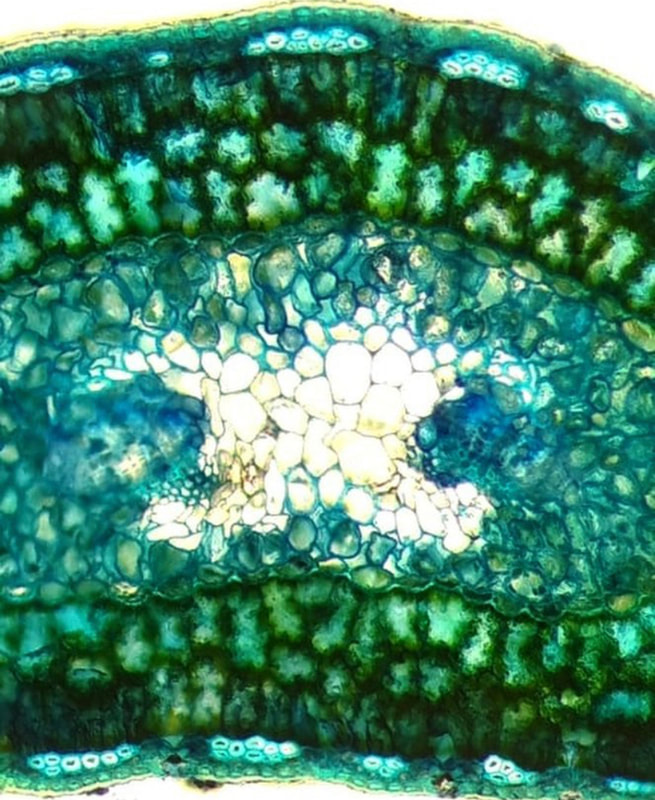

The Canadian Shield is comprised of primarily a boreal forest ecosystem, which is a biome dominated by many conifer trees, including those in the pine family (Pinaceae). These trees have needle-like leaves which are specially adapted for the harsh climate of northern Canada. These leaves have a thick waxy coat (cuticle) on the surface, and abundant fibers to support the leaf. The green cells pictured here in this section are photosynthetic, and the central cells contain the transfusion tissue, which moves nutrients between the vascular bundles and photosynthetic cells! This anatomy is common among the gymnosperms (cone-bearing plants), such as Pinus banksiana (micrograph) and the closely related Pinus contorta (photograph).

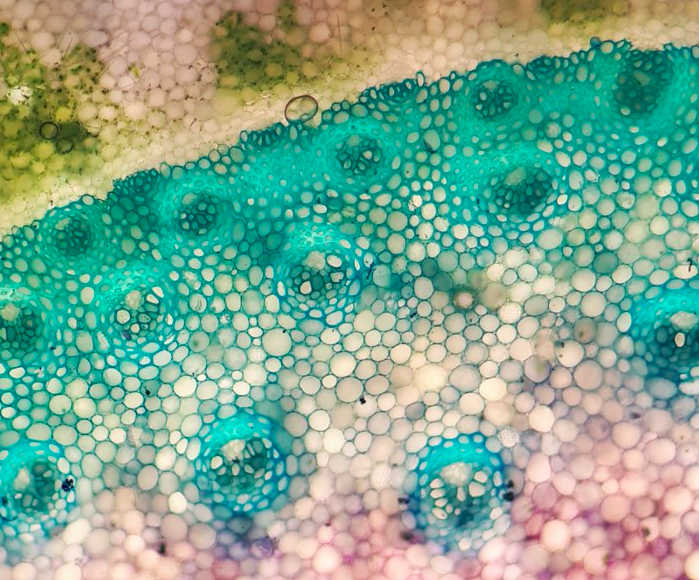

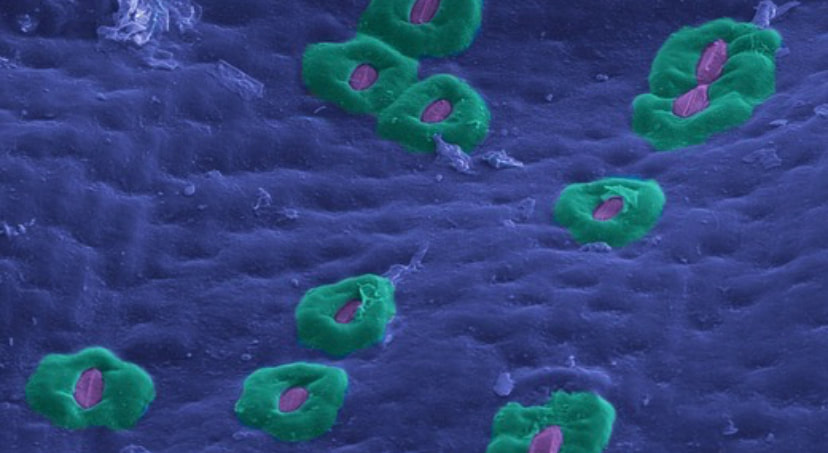

So how do plants regulate their intake of carbon dioxide and release of oxygen? Stomata are omnipresent across the land plant groups (except the liverworts), and function as pores on the epidermis (coloured blue in this image). Stomata are compound structures comprised of two guard cells (purple) and typically surrounded by subsidiary cells (teal) in many species. The guard cells regulate the opening (apertures) of the stomata. While open, stomata release oxygen produced as a byproduct of photosynthesis, and take in carbon dioxide. The guard cells open and close using water pressure - influx of water into the guard cells stretches the cell walls, and opens the aperture. Stomatal opening and closing occurs as a response to many different environmental stimuli. Pictured here is a drought-adapted plant Sansevieria trifasciata, which has large subsidiary cells to mitigate water evaporation from the apertures!

|

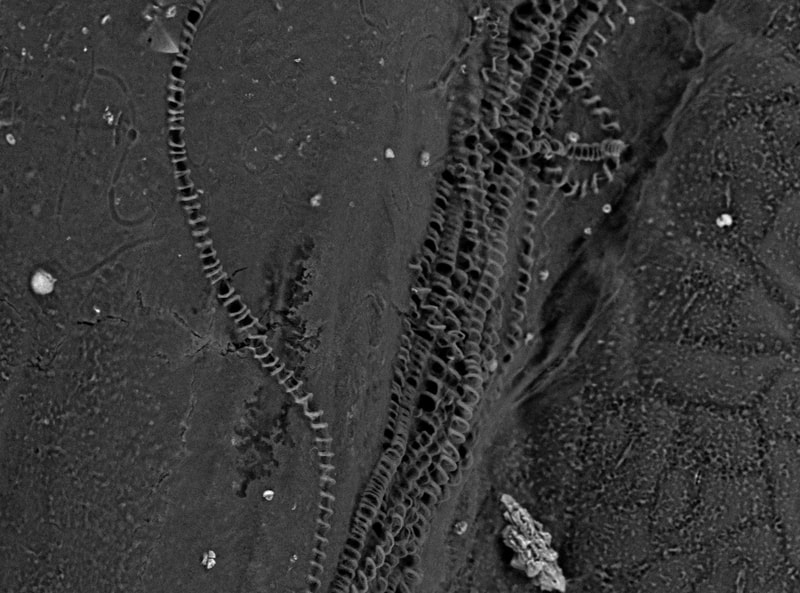

So, how does a plant transport water? One of the most important milestones in land plant evolution was the development of vasculature, which is comprised of xylem (water transport) and phloem (sugar transport) and is ubiquitous throughout the lycophytes, ferns, gymnosperms (including conifers), and flowering plants. Flowering plants, like canola, have developed a more efficient mode of water transport using vessel members within the xylem, which are elongated cellular channels that are reinforced by ring-like thickenings (like our trachea!). Pictured left are the vessel members in the veins of canola leaf using environmental scanning electron microscopy!

|

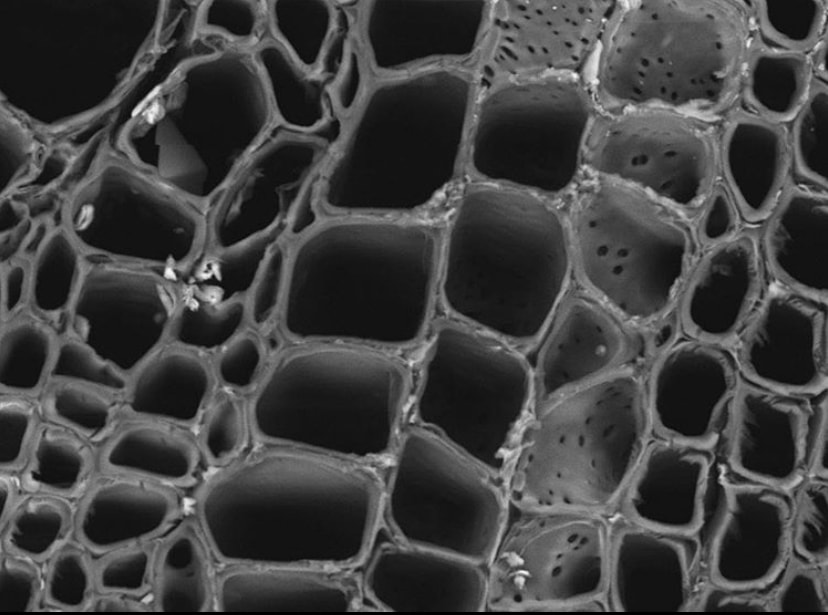

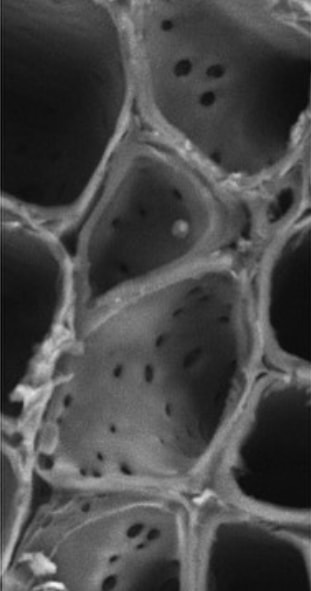

On the left, we spoke about plants and their ability to transport water vertically, but how does water move horizontally through the stem? Imaged on the right is a cross section of a canola stem, with vessel members viewed from top-down using scanning electron microscopy. The structure in the right most image are the vessel member walls wrapping around a xylem ray. The xylem ray is elongated horizontally, and transports water laterally through the stem. The small pores of the vessel member wall are pits, and allow water permeation between the xylem rays and the vessel members. This allows a continuous flow of water both vertically and horizontally to supply water equally to each and every tissue in the plant!

|